The snow came softly, silently, unexpectedly, the pure white flakes tumbling down in the early evening time. As we get older, we begin to grow wary of snow; we view it with mistrust. We no longer embrace it with the same joy and delight as we did when we were children, and yet for all that I felt a tingle of excitement as I watched it fall from the sky.

It’s wasn’t long till the berried holly trees in the yard was radiantly white, the rich red of the berries and the yellow and green of the leaves layered with the newly-fallen snow. It was the same again with the Scot’s pine, the vivid winterish green of its needles suddenly transformed in the wonder of the moment.

Our reader in sixth class was The Road to Reading. One of the pieces in it was all about snow by Alexander Smith. According to him: ‘Winter in the country without snow is like summer without the rose. Snow is winter’s specialty, its crowning glory, its last exquisite grace.’

As I watched the snow come down, I could readily identify with his sentiment that the falling of the first snowflake is an event in itself, something that catches the imagination and takes hold of it. Even the dullest of mortals, he maintained, finds some sort of pleasure in the new soft, white world that the snow bestows upon him.

As I watched the snow come down, I could readily identify with his sentiment that the falling of the first snowflake is an event in itself, something that catches the imagination and takes hold of it. Even the dullest of mortals, he maintained, finds some sort of pleasure in the new soft, white world that the snow bestows upon him.

I rose early the next morning, the snow lying thick and heavy in yard and garden and field, the sun looking ancient and wintry, shedding long slanted beams across the snowy field by the house, the thorn hedges become marvellous, magical tangles of white. The light of the sun of a kind honoured by the druids, a kind that might have flooded the long stone passageways and chambers aeons ago.

Later in the morning the snowy boughs of the old sycamore in the garden were etched against the radiant china blue of the sky, the mountains to the north and the south become whitened citadels again. The great old ash tree by the roadside and the chestnut tree in the corner of the field, were snowy too, the sun lighting up their bare branches so that they looked more beautiful still.

The oldest fir trees fringing the grove were Alpine postcards against the sky. The more I stood and looked at them, the more it seemed that they were revelling in the moment: how many snowy winters they had seen come and go was anybody’s guess.

Greenfinches and goldfinches fluttered round the feeders that hung from the old sycamore, robins and blackbirds and sparrows descending on the bird table, the mistle thrush returning to sample a few holly berries from the tree in the yard.

I don’t know why, but the little birds reminded me of Emily Dickenson’s poem ‘Hope is the T-hing With Feathers. She imagines hope as a little bird that perches in the soul and that despite its small size can brave the fiercest of storms. It is selfless and giving for according to the poet ‘Yet never in Extremity, it asked a crumb of me.’

As morning slipped into afternoon, the sun made the snow on the trees more beautiful still. We loved building snowmen as children but I contented myself with going for walk with my big black Labrador, Sweep: the old ringed fort in the distance looking as though it was etched in white relief against the translucent blue beyond.

I thought of a winter in the early sixties: the snow so soft, so deep that we seemed to sink into it as we made our way to the old yellow farmhouse where my Aunt Mag lived with her husband and family. Here there was the warmth of the great open fire, the comforting scent of the pine logs, the steady measured beat of the fine American wall clock. The Kerry cows cosy and snug in the byre, the cobbled yard lost beneath the blanket of snow.

As I walked with Sweep, I was stopped in my tracks by the sound of a robin singing in the hedge. I couldn’t fathom why he thought of singing on such a cold and wintry day, his sweet melodic warble more and more resonant in the hush of the snow. He had reasons of his own to sing and I was glad that he had: his song like an anthem of hope.

Later I came upon an otter swimming and diving in the river, the latter rich in reflections of snowy trees and peaks. I stood spellbound by the swimmer, his movements purposeful and fluent, his whiskered head held above the water every now and then. My canine companion, equally intrigued, somehow resisted the impulse to bark. The otter making his way upstream in the very middle of the river.

As for me, it was as if I had found a little bit of magic and so I did not stir till the otter was out of sight.

Snow and robin and otter, surely some of winter’s finest, so that when I headed home at last, I did so with a lightness of step and a lightness of heart, thankful as I was for all that I had seen and heard: my companion still running and romping before me with the same delight as before. n

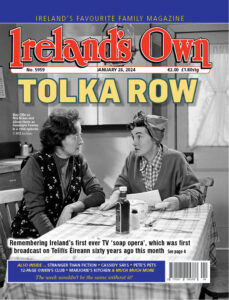

Photo: Caught in snow-drift in Templeogue, 29/12/1962 (Part of the Independent Newspapers Ireland/NLI Collection).